Lana Whiskeyjack’s art tells a story, stories deeply personal to the artist who now makes her home in Ashmont.

“I always feel vulnerable when I’m sharing, especially with the art that exposes my own heart and spirit because it also exposes my family. It’s almost like you’re nude, you’re so vulnerable,” she says with a laugh, of showing her work at this weekend’s Heritage Festival art show.

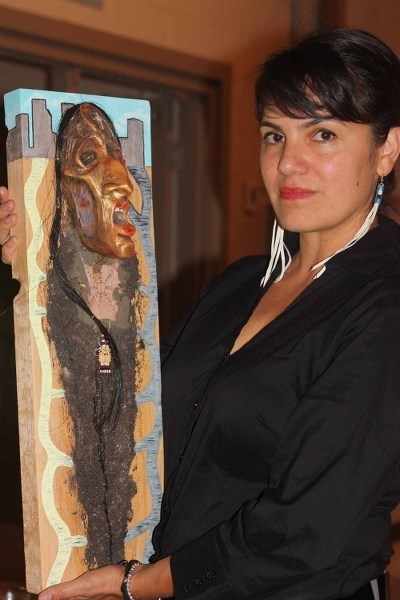

But she shares her art in the hopes that it will create discussions, or spur the uncomfortable conversations that people need to start having, as she points in particular to one mixed media piece, called Lost My Talk.

“It is dedicated to my uncle. He lived in the streets, he walked the streets in St. Paul. This is a piece that’s dedicated to understanding him as a survivor, an Indian Residential School survivor.”

But before Whiskeyjack knew anything about her uncle’s history, she knew his personality, his fun-loving nature.

“He was my favourite uncle – he taught me how to play cards, he taught me how to use a knife, he taught me how to throw a punch!” she recalled, saying her uncle was “brilliant” and was even fluent in Latin from his time spent as an altar boy at Blue Quills when it was a residential school.

But his experience at the school left deep wounds in him, she said, adding, “When he left, he was full of rage and anger, which determined his life living on the streets.”

He would end up controlled by his addictions and passed away in 2000, while still in his early 50s.

“This piece was about honouring a man who was feared by our community,” she said, noting her uncle was in and out of jail, with tattoos that he’d gotten through the years, one of which was a cross on his forehead. “Being a tall, brown man, he was a bit intimidating for a lot of people in our society. They were afraid.”

The piece speaks to George Whiskeyjack’s life and personality, with the face marked by the cross on his forehead, horse hair, and soil trailing down as the body, soil taken from Blue Quills College and from the streets of Edmonton. Fifteen years after her uncle’s passing, Whiskeyjack also lost her younger uncle, Kenny Whiskeyjack, to addiction.

What people might not have seen or realized was that her uncles, both of whom people might refer to as “backstreet boys,” were loving, and leaders in their circle of friends. No outsiders could know the strong sense of community and friendships that exists among these groups, she said.

Three generations of Whiskeyjack’s family was affected by residential schools, and it affected her own life too, as she spent time in different homes, including living in foster care before she came to live with her grandmother in Saddle Lake.

Throughout it all, art was a constant.

“Art was one of the ways that helped me process and communicate in ways I couldn’t verbally do.”

Her mother always joked she could never get her damage deposits back on rental property, because Whiskeyjack was forever drawing on the walls. And when she would find earth in the cellar, she would sculpt with that, which became her first love and which she would go on to receive formal training for at Red Deer College.

When asked how she was able to overcome the challenges and intergenerational trauma posed by her family’s experience of residential schools, Whiskeyjack is reflective.

“I think because I was in different homes, that showed me what stability looked like, that nurtured stability and understanding,” she said. “I was lucky that I had really good experiences with people that loved me.”

Her grandmother was also “fiercely supportive and loving,” a pillar of her community that grounded young Whiskeyjack as she grew up, a love reflected in another of her paintings of a grandmother, mother and child, embracing each other.

Whiskeyjack is now taking her doctorate in Indigenous Studies in Blue Quills, where she is studying decolonization. It’s a process that she hopes other people explore and come to understand through her work.

“That’s what art does to me – it makes you think and question, and shift your mind. If people have the courage to ask questions and to start talking, to me, that’s helpful,” she says, adding - “That’s growing and healing.”